The Poem “Ông Đồ” by Vũ Đình Liên

Vinh-The Lam, M.L.S.

Librarian Emeritus

University of Saskatchewan, Canada

In 1936, the poem “Ông Đồ” (The Master) by poet Vũ Đình Liên, published for the first time on the periodical Tinh hoa (The Elitist), was an instant success, and has been enjoyed by several generations of Vietnamese poetry lovers until now. Vũ Đình Liên’s reputation as a poet was forever solidified by this unique one-hundred-word poem. This article tries to introduce this famous poem to the generation of English-fluent overseas Vietnamese youth.

Poet Vũ Đình Liên (1913-1996)

The Original Poem in Vietnamese

Mỗi năm hoa đào nở

Lại thấy ông đồ già

Bày mực tàu, giấy đỏ

Bên phố đông người quạ

Bao nhiêu người thuê viết

Tấm tắc ngợi khen tài

Hoa tay thảo những nét

Như phượng múa, rồng baỵ

Nhưng mỗi năm, mỗi vắng

Người thuê viết nay đâu

Giấy đỏ buồn không thắm

Mực đọng trong nghiên sầụ

Ông đồ vẫn ngồi đấy

Qua đường không ai hay

Lá vàng rơi trên giấy

Ngoài trời mưa bụi baỵ

Năm nay đào lại nở

Không thấy ông đồ xưa

Những người muôn năm cũ

Hồn ở đâu bây giờ?

English Translation of the Poem

Every year when the cherry blossoms

Again, the old master re-appears

Displaying his Chinese black ink and red writing paper

On the sidewalk of a crowded street.

Innumerable clients who hired him to write,

Smacking their tongue, all admired him for his calligraphic talent

His skillful hand has created artistic letters

As beautiful as the dancing phoenix, as the flying dragon.

But then, year after year, fewer and fewer clients

Where are they now?

Saddened unused red paper losing their brightness

Dried out ink depositing at the bottom of the blue untouched ink slab.

The old master still sitting there

Totally ignored by passers-by

Yellow leaves falling down on the paper

A drizzle falling down from the open sky.

This year the cherry blossoms again

The old master is not here

All these people of the old days

Where are their souls now?

Interpretation of the Poem

Vũ Đình Liên has borrowed Tang Poetry Wujue 五 絕 [1] form to write this poem, which, instead of including just one quatrain of 4 lines of 5 words, contains exactly 100 words arranged in 5 quatrains, each having 4 lines of 5 words.

In the first quatrain, the author set the stage for Act I of this 5-act drama for the main cast, The Master, introducing the time and space of his working environment. The time was springtime and Tết, the greatest holiday of the year, was approaching with the cherry blossoming. The whole nation was in a festive mood and every house was preparing to welcome Tết. The indispensable decorative pieces for the house were the “câu đối đỏ” [2] (parallel sentences on red paper). And that was exactly what The Master could provide for a fee. The space for his working environment was the sidewalk of a crowded street where he displayed his working tools: red paper sheets and Chinese black ink. The Master was ready for action.

The Master on the Sidewalk – Source: Internet

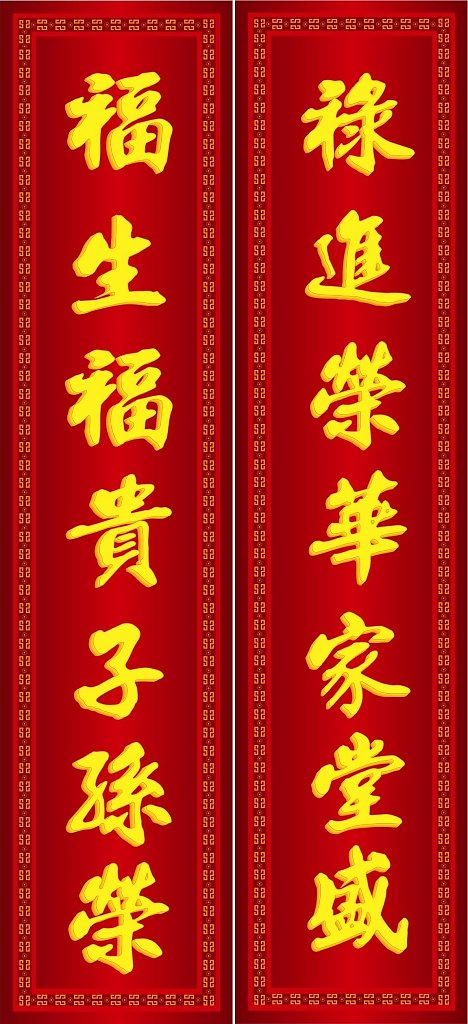

In the second quatrain, or Act II, the author presented The Master In Action. Many passers-by stopped and asked for his services. Almost all sentences asked for were conventional, sometimes just the letter “Phúc = Happiness.” The valuable creative contribution of The Master was his calligraphic talent in providing “dancing phoenix, flying dragon” artistic parallel sentences or letters, all in Chinese characters, such as:

(The parallel sentences read, from right to left, and from top to bottom:

Lộc tiến vinh hoa gia đường thịnh = Wealth with honor and good things making family prosper

Phúc sinh phú quý tử tôn vinh = Good fortune bringing wealth and honor to the offspring

The character in the red diamond reads: Phúc = Happiness, Good fortune)

In the third quatrain, or Act III, the fortune of The Master started to be going down together with the beginning of the decline of the traditional Chinese-character-based national educational system replaced by the French-introduced Quốc-ngữ-based (with Roman alphabet as Vietnam having become a French colony) national educational system. People no longer needed these parallel sentences in Chinese characters. The Master’s client base dwindled. The unused red paper sheets were losing their brightness and the untouched Chinese black ink were dried out at the bottom of the ink slab.

In the fourth quatrain, or Act IV, The Master still tried to hang on, but the sad reality of the total collapse of the old system really set in. He was totally ignored by people, who no longer had needs for his services. The red paper sheets not only lost their brightness but also buried in yellow dead leaves. And his modest working place on the street sidewalk now became invisible by the drizzle falling down from the open sky.

In the fifth and last quatrain, or the Curtain Act of this 5-act drama, the author pointed out the indifference of Nature. The cherry blossomed again, just like the previous years. But this time The Master was nowhere to be found. He was gone, like his Chinese-character-educated generation. And so was that traditional cultural way of life. We could feel or hear the author’s sigh of regret for a time and a way of life forever lost: Where are their souls now?

Notes:

- Wujue poem form, online document accessible full text at this URL: http://forums.familyfriendpoems.com/topic.asp?TOPIC_ID=105947

- One of the most famous folk sayings about Tết: “Thịt mở, dưa hành, câu đối đỏ; cây nêu, tràng pháo, bánh chưng xanh,” (Fat meat, pickled onions, parallel sentences on red paper; new year pole, strings of firecrackers, square rice cakes wrapped in green banana leaves).