THE MEANING OF TẾT IN VIETNAM

PHẠM TRỌNG LỆ

(This paper was originally prepared as a 50-minute talk and given at the invitation of the VAA Cultural Affairs Office in Saigon in December 1972. The part on the faithful dog Hachikō is from Wikipedia added for the coming new lunar year of Mậu Tuất).

TỂT NGUYÊN ĐÁN AND THE LUNAR CALENDAR

To begin with, I should like to look at the meaning of the term Tết. Tết derives from the word tiết, which means season, climate. It’s used in such Vietnamese expressions as thời tiết (weather) and tứ thời bát tiết (the seasonal divisions of the year, the beginning of the seasons, the equinoxes and the solstices).

The term Tết nguyên đán denotes the new year festival that falls on the first day of the first month of the lunar year, and lasts for at least three days. In the term nguyên đán, the word nguyên means first, and the word đán, early morning. Taken together, they mean the first moment of the first day, in the first month of the first year.

Tết coincides with the Lunar Calendar (âm lịch), which, according to Chinese history, has been in use for over 4,000 years. In this calendar twelve animals represent the twelve months, each corresponding to one turn of the moon around the earth. Actually, each lunar year is composed of twelve months and ten days. Then for every two and a half years, there is a leap year of 13 months. The cycle of 12 years ‘giáp’ uses the same animals to denote the years.

Ten can Twelve chi

giáp tí ‘rat’

ất sửu ‘buffalo’

bính dần ‘tiger’

đinh mão ‘cat’

mậu thìn ‘dragon’

kỷ tỵ ‘snake’

canh ngọ ‘horse’

tân mùi ‘goat’

nhâm thân ‘monkey’

quý dậu ‘rooster’

tuất ‘dog’

hợi ‘pig’

The lunar year coming to an end is đinh dậu, the year of the rooster, and the New Year is mậu tuất, the year of the dog. which begins on Friday, February 16, 2018. It is difficult to know when the Vietnamese started celebrating Tết. This custom may date back to the first century when the Chinese are first believed to have taught our people their customs.

WHAT THE DOG MEANS (from Wikipedia)

The dog is known to have many qualities: faithful, loyal, obedient, and intelligent.

One of the most famous dogs is Hachikō who was born November 10, 1923 and died March 8, 1935, an Akita dog born on a farm near the city of Odate, Akita Prefecture, Japan. He is remembered for his remarkable loyalty to his owner, Professor Hidesaburō Ueno, a professor in the agriculture department of Todai or Tōkyō daigaku (The University of Tokyo), whom he continued to wait for over nine years following the death of his master. Well after the professor’s sudden death the dog continued to wait for him at the railroad station. Hachikō got the attention of other commuters who regularly used the Shibuya train and had seen the dog and the professor together. After the dog’s story was told on the paper Asahi Shimbun people started to bring Hachikō food during his wait. Hachikō became a national sensation and his faithfulness became a national symbol of loyalty in Japan. After his death, his remains were cremated and his ashes were buried in Ayoama Cemetery, Minato, Tokyo beside those of his beloved master, Professor Ueno.

Fig. 1. The dog Hachikō in the story.

In 1934, a bronze statue in his likeness was erected at Shibuya Station. During the Second World War, the bronze statue was recycled for the war effort. In August 1948, a new statue was commissioned. Today at the Shibuya station, the Hachikō Entrance/Exit stands the statue of the loyal dog. It is also a popular meeting place for boys and girls and tourists. In 2015, the Faculty of Agriculture of the University of Tokyo constructed a bronze statue depicting Ueno returning to meet Hachikō. Each year on March 8, Hachikō devotion is honored at Tokyo’s Shibuya railroad station.

Fig. 2. Hachikō welcoming his master.

HOW THE VIETNAMESE PREPARE FOR TÊT

Tết Foods: About ten days before Tết, families seem to be busy preparing for the celebration. Mothers and grandmothers prepare special Tết foods and men and children gobble them greedily and gratefully. Among the favorites are bánh chưng (glutinous rice cake with pork, mung beans wrapped in dong (Phrynium placentarium) leaf, bánh tét in cylindrical shape, which is more popular in the South, and bánh dầy (glutinous rice cake) served with giò (pressed pork pie wrapped in banana leaf), giò thủ (head pressed pork equivalent to German head cheese Presskopt), chả (baked pork paste), and thịt kho (caramel pork cooked in nước mắm), cá kho (low-fired fish), dưa giá (pickled bean sprouts), dưa cải xanh (pickled mustard green cabbage), dưa hành (pickled scallions), củ kiệu (pickled small scallions), mứt (fruit preserves), dưa hấu (water melons) and other fruits such as oranges, tangerines, bananas, pineapples and grapefruits, custard apples (mãng cầu), coconuts (dừa), papayas (đu đủ), mangoes (soài), kumquats (quất)…

Story of Bánh chưng and Bánh dầy:

Once upon a time it was believed that the earth was square and flat and the sun round. These two cakes represent the shape of the earth and the sun.

Legend has it that the 6th King of the HÙNG dynasty had 24 princes among whom he would choose one to succeed him to the throne. On Tết that year, the King summoned the princes and gave them a test. “Tomorrow morning, the one with the best offering will be given the throne,” he said.

While the elder princes were looking for precious jewels and rare foods, the youngest simply took a long slumber. In his dream, he was told by an immortal how to make these two cakes. Upon awakening he did exactly as he had been told.

Fig. 3. Bánh Tét.

To everyone’s surprise, his offering got the first prize. The King liked the cakes because the ingredients

were simple Fig. 4. Bánh Chưng.

for almost every farmer to make from the produces and the animals on his farm. Also, the round shape of the bánh dầy represents the shape of the sun and the square shape of the bánh chưng the earth.

Inside Decorations: The children look forward to Tết because they are allowed to wear their new clothes and are given tiền lì xì (luck money) in crimson paper envelopes.

No one but grandpa is allowed to prepare the ancestors’ altar. He can be seen shining his brass candlesticks and his incense burner, cleaning with loving care his well-kept tea set, pruning the chrysanthemums, peach blossoms and apricot flowers.

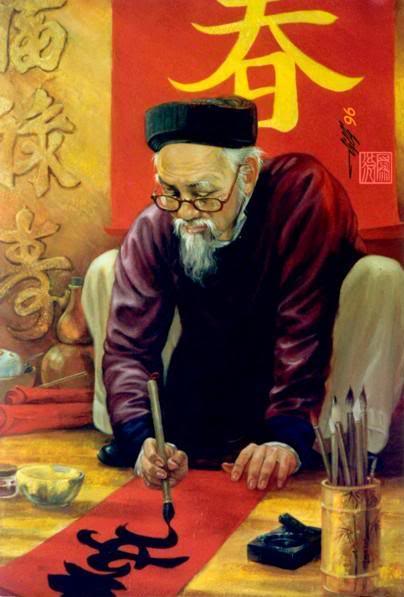

Now when everything is in its proper place on the altar, grandpa places a piece of red scroll on either side; each contains a handwritten sentence. I’d like to devote a few words on this dying art of calligraphy called câu đối (parallel sentences).

Fig. 5. Family making Bánh Chưng.

Toward the end of the lunar year, an old Confucian master can be seen at the corner of the village market, sitting on a small wooden bed. He writes the sentences for customers to hang in their houses during Tết. The handwritten wishes for luck, prosperity, or good fortune balance and contrast each other in sound and thought. Some are considered miniature literary masterpieces.

This somewhat somber and nostalgic poem by a pre-war po

et pictures the traditional scene.

Ông Đồ

Vũ Đình Liên (1913-1996)

Mỗi năm hoa đào nở Fig. 6. Vũ Đình Liên

Lại thấy ông đồ già

Bầy mực tầu giấy đỏ

Bên phố đông người qua.

Bao nhiêu người thuê viết,

Tấm tắc ngợi khen tài,

“Hoa tay thảo những nét,

Như phượng múa rồng bay.”

Nhưng mỗi năm mỗi vắng

Người thuê viết nay đâu?

Giấy đỏ buồn không thắm,

Mực đọng trong nghiên sầu.

.

Ông đồ vẫn ngồi đấy,

Qua đường không ai hay,

Lá vàng rơi trên giấy,

Ngoài trời mưa bụi bay.

Năm nay đào lại nở,

Không thấy ông đồ xưa,

Những người muôn năm cũ,

Hồn ở đâu bây giờ?

The old calligrapher

Every year, when peach blossoms were blooming,

The old Confucian master was seen again,

Arranging his slabs of Chinese black ink among scrolls of red paper

Over the sidewalk where strolled by crowds of passers.

So many customers hired him to write sentences

Loudly expressing their admiration for his talent

In his skillful handwriting with masterly strokes

As free as the dance of the phoenix and the flight of the dragon.

Scarcer and scarcer every year

Where are his customers now?

His melancholy paper was no longer bright red

His ink was getting low in the sad ink-well.

The old master was still there

Ignored by passers-by.

Dead leaves were falling on his paper

While fine rain was blowing outside.

The peach blossoms are blooming this year

But the aged master is no longer here.

The old-timers of bygone days,

Whither are their souls fading away?

(Translated by Le Trong Pham, 1972)

NOTE:

While doing additional revision for this article, this writer came upon very fine translations, some of which with rhymes, listed in the Appendix:

- Ông Đồ – The Confucian Scholar (Kim Vũ), Việt Nam Những Áng Thơ Tuyệt Tác: Vietnamese Poetry: A Sampler, 2003, pp. 95-96)

- Ông Đồ – The Calligrapher by Thomas D. Le (thehuuvandan.org/vietpoet.html#vudinhlien) 12 January 2005.

- The Master by Vương Thu Trang (http://www.huongdaoonline.net.org/ong-do-vu-dinh-lien)

- The Old Calligrapher by Huynh Sanh Thong in An Anthology of Vietnamese Poems from the Eleventh through the Twentieth Centuries. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1996, p. 320-321.)

Outside Decorations: By the 30th of the 12th lunar month at the latest, country people plant a cây nêu or bamboo pole in front of their houses. Attached to the top are multicolored pieces of cloth, and some small tablets (khánh) made of baked clay that would chime when the wind blows. They believe the area where the nêu is planted is protected by Buddha from the harassment of devils.

This superstition is dying out, particularly in the cities, where most houses do not have extra space to plant these tall poles. Some people also display sketches of bows and arrows to ward off the evil spirits.

TẾT TIME

Lễ Ông Táo (the worship of the Kitchen God): Tết begins unofficially with the worship of the Kitchen God on the 23rd of the 12th lunar month. A family’s kitchen god is believed to report to the Jade Emperor (Ngọc Hoàng) on the activities of that family in the year. The offerings made to him are usually betel leaves, areca nuts, rice alcohol, steamed sticky rice and chicken. The offerings also include a carp, which is said to be used by the Kitchen God the fly to Heaven.

A Legend: In the old days there lived a happy couple. Being very poor, the husband had to leave home to work in a region far from his village. During his long absence, his wife, who thought he was dead, married a wealthy man. One day the old husband suddenly appeared at the gate as a beggar. She fed him a good meal. As they were reminiscing over past times, the second husband returned after a hunting trip. She hid the old husband in the haystack, which the second spouse burned to make fertilizer—something farmers often do. As a result, the unlucky first husband was burned to death. Ashamed of being disloyal to her husband—or, more correctly, husbands—the lady jumped into the flames and killed herself. The second husband witnessed the tragedy, and heart-broken, jumped into the fire as well. The Emperor of Jade, as the story goes, heard of their loyalty and appointed them “genii of the kitchen” (vua bếp) whose duty was to report to the Jade Emperor what was happening in the household during that year.

So when the Kitchen God is sent to Heaven on behalf of all three, paper hats and boots are burned on this day. Also, it is interesting to note that the genii are pictured without trousers. The simplicity and unconventionality of their attire is understandable when you realize that in certain parts of Viet-Nam, men still hunt game and do work in the field that the wearing of pants would hinder.

Đêm Trừ Tịch and Lễ Gia Tiên (New Year’s Eve and Worship of the Ancestors): New Year’s Eve sees the family members gathering around the boiler of Bánh Chưng talking and waiting for the coming of the New Year. At 12 o’clock sharp, everyone in the family approaches the altar, the eldest first, the youngest last, to worship their ancestors.

Firecrackers used to be fired to repel the evil spirits and to welcome the new executive divinity, Thần Hành Khiển. Now on New Year’s Eve, pagodas and temples hold religious services for the public to give thanks to God, Buddha or other deities, and to pray for good luck in the coming year.

Hái lộc (Picking Buds): On their way from the pagoda on Đêm Ba Mươi, New Year’s Eve, people collect a twig of young buds or a branch of flowers. This is called the cành lộc or twig of luck. It’s put in a vase – on the home altar.

Xông Nhà (the First Visitor to the House):

A person of pleasant disposition, after attending New Year’s Eve ceremony, is selected to be the first person after midnight to visit the home. Such person would bring luck all year round to the family the rest of the year.

Xuất Hành (the First Trip of the Year):

The first trip of the year should be to a place where one may meet good spirits rather than evil ones. To determine the right direction, the calendar or the fortune teller is consulted.

Chúc Tết (Well-Wishing). Here are some typical wishes heard on the occasion of Tet:

-To a newly-wed couple: I hope you and your wife have a baby boy early this year and a baby girl toward the end of this same year, and that you have five or ten times as much money and luck this year as last. (Chúc anh chị đầu năm sinh con trai, cuối năm sinh con gái, phát tài sai lộc bằng năm bằng mười năm ngoái).

Those concerned with the problem of overpopulation may be practically dismayed by such a wish. In Viet-Nam, however, prosperity (phước) is believed linked with fertility. As a matter of fact, the God of Fortune (ông Phúc) is often shown holding a baby boy in his arms.

-To an unmarried girl: (This year we wish to attend your wedding party and have betel and alcohol).

Don’ts during Tết.

Don’t get upset during Tet, because an outburst of profanity would bring ill luck for the whole year. Avoid mentioning such taboo words as con khỉ (monkey), con hùm (tiger), con chó (dog), con mèo (cat).

Try not to break anything during the first day of Tết. This is another sign of bad luck.

Don’t dress in white, the color reserved for mourning in Viet-Nam.

Don’t sweep your house on the first day of Tet. If you do, you sweep your wealth away!

The story goes that there was once a businessman who was offered a tiny lucky pet monkey by a beautiful woman, and subsequently became rich. Then, on the first day of a new year, he beat his monkey and the pet hid itself in the trash, and was swept away. Once his lucky charm was gone, the man turned poor again.

In other words, one tries to behave as correctly as possible during Tet time, hoping of course to set a good pattern for the whole year.

THE MEANING OF TẾT

Tết is the time for the ladies in the family to show their talent in cooking. It’s also a chance for the daughters to learn the culinary art from their mother and grandmother. (Among the four virtues (tứ đức) of a woman brought up in Confucian teachings, công, proper management, comes first. The other three virtues are dung, ngôn and hạnh—proper demeanor, proper speech, and proper behavior.

In the countryside, the harvest and new planting season are over with, and the young girls have a chance to test the young farmers’ abilities in singing and dancing at the Hội Tết (Tết Fair).

Tet is a time for the Vietnamese to strengthen the link with the past by worshiping their ancestors, and paying respect to their elders, masters and benefactors.

It is a time to take a break from work and have fun, and think of relatives and friends. Serious-minded individuals also take this occasion to review the things that have been done, and look ahead to the New Year.

It is time to realize that one is one year older, and hopefully more mature. A pretty young lady looking at herself in the mirror is happy to see that she is becoming prettier. A baby born a few days before Tet is told to be two years old after Tet comes. Grandpa adds one more year to his record of wisdom and longevity.

During Tết time, houses are cleaner, streets more colorful, men better-dressed and better-mannered, and ladies more attractive. Even two business adversaries who meet with each other will probably wish the other good luck and prosperity. Tết is a time to make people happy with your wishes, and to witness the blossoming of the peach flowers, the orchids, the chrysanthemums.

It is with these mixed feelings of anxiety and hope, joys and expectancy that each of us welcomes Tet in our own way. Whether Tết means much or little to us, it remains our most traditional holiday, the year’s most important festival and celebration for the renewal of heaven and earth for the majority of people in Viêt-Nam as well as for those of Vietnamese origin around the world when everyone celebrates joy and hope in tune with nature and the universe.

APPENDIX

Note to Readers: While editing this old paper, I came across some very fine translations of the poem “Ông Đồ” by Vũ Đình Liên. I hope you’ll enjoy the translations as much as I did.–PTL

- The Old Calligrapher

Each year when peach trees blossomed forth,

you’d see the scholar, an old man,

set out red paper and black ink

beside a street where many passed.

The people who hired him to write

Would cluck their tongues and offer praise:

“His hand can draw such splendid strokes!

A phoenix flies! A dragon soars!”

But few came, year after year—

Where were the ones who/d hire his skill?

Red paper, fading, lay untouched.

His black ink caked inside the well Fig. 7. An old calligrapher

The aged scholar sat there still;

The passers-by paid him no heed.

Upon the paper dropped gold leaves,

And from the sky a dust of rain.

This year peach blossoms bloom again—

no longer is the scholar seen.

Those people graced a bygone age—

Where is their spirit dwelling now?

Translated by Huynh Sanh Thong (1996)

- The Confucian Scholar

Each year, at the time of cherry blossoms

An old Confucian scholar comes

Displaying his China ink and red sheets

On the sidewalk of a busy street.

People pay him to write scrolls for Tet

Admiring his deft fingers

“Your fine calligraphic characters

Are like the flying dragons and soaring phoenixes.”

As the years went by and by

Fewer people came to ask

His red paper seemed pale and sad

And ink is his plate settled to dry…

The old scholar still sat there by the wayside

To the indifference of passers-by

Dead leaves fell on his sheets

And a drizzle covered the sky.

It’s the time of cherry blossoms once more

But the old Confucian scholar is no more

The spirits of people a thousand years past

Where are they now, I wonder.

Translated by Kim Vũ (Vũ Mạnh Phát) (March, 2003)

- The Calligrapher

Just as the pink cherry blossomed each year

The old scholar was sure to reappear

With China ink and red paper in scrolls

Amidst the swelling crowds that surged and rolled.

So many people paid him handsomely

For his talent that they admired dearly,

The flourishes of his accomplished hand

That wrought dragons and phoenixes on end.

Each passing year saw fewer people come.

Where were they all who paid him so handsome?

Now his paper had lost its crimson red,

His ink dried out in its sad forlorn bed.

At his old place sat the calligrapher

Amidst the hustling crowds without a stir.

Some yellow leaves fell dead on his paper,

And from above drizzle flew in a whir.

This year the cherry blooms light pink again,

The old scholar is found nowhere in vain.

Of all those people lived in days of yore

Where are they now, where’er forevermore?

Translated by Thomas D. Le (12 January 2005)

- The Master

Peach blossoms bloomed very spring

There again, old master came

With red paper and black ink

On a street, where people claimed

They claimed to buy his writings,

And all praised him while buying

“Just a mere move of his hand

Turns strokes into phoenix dance!”

But fewer buyers came each year

Admirers, where did they go…?

Unused ink laid like black tears.

Red paper dulled in sorrow…

That old master just sat there

Among those who did not care.

On the dull red fallen dead leaves;

There fell soft rain with slight grief

Another peach blossoms’ spring

Yet the old master is not there.

Oh, where are they wandering

Old folks’ souls we all forgot?

Translated by Vuong Thu Trang

(January 21, 2015)

Posted in http://www.huongdaoonline.net/ong-do-vu-dinh-lien/ ■

Photo Credits

Fig. 1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hachik%C5%8D#/media/File:Hachiko.JPG

Fig. 2. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hachik%C5%8D#/media/File:Hachi_Ueno.jpg

Fig. 3..https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/B%C3%A1nh_t%C3%A9t#/media/File:Banhtet.jpg

Fig. 4. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%E1%BA%BFt#/media/File:Banh_chung_vuong.jpg

Fig. 5. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%E1%BA%BFt#/media/File:Goi_banh_chung.jpg

Fig. 6. https://phamquynh.files.wordpress.com/2014/01/vu-dinh-lien_ong-do.jpg

Fig. 7. http://media.bizwebmedia.net/sites/76048/data/Upload/2014/11/ongdo.jpg

Bibliography

-Nhất Thanh (Vũ Văn Khiếu), Đất Lề Quê Thói: Phong Tục Việt Nam. Saigon: Cơ Sở Ấn Loát Đường Sáng, 1968. Tết Nguyên Đán, pp. 296 -308.

-Truyện con chó trung thành Hachiko: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hachiko

– See also, Richard Gere in 2009 film Hachi:A dog’s Tale in YouTube.

-Tết Nguyên Đán

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tết

-Further note on Têt fare: For the gourmets who like giò thủ and various ways how head cheeses are prepared in various countries, see:

En.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Head_cheese

Vi.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giò_thủ

-For serious researchers:

Pierre Huard and Maurice Durand. CONNAISSANCE DU VIỆT-NAM. Paris and Hanoi: École Française D’Extrême-Orient, 1954, 356 pp.

Henri Oger. Introduction générale à l’étude de la technique du peuple annamite, essai sur la vie matérielle, les arts et industries du people d’Annam. Paris: Geuthner, 1908. Line drawings of craft techniques of the Vietnamese people in Tonkin. This title in multiple volumes may be found in large libraries. A brief look at sample pages of the sketches can be found at:

Source: Cindynguyen.com/2015/03/22/intro-to-the-henri-oger-project-on-reading-a peripheral-text

-Nguyễn Ngọc Bích, Tết: The Vietnamese New Year. Arlington, VA: East Coast Vietnamese Publishing Consortium, 2004. 144 pp. Contact: Cành Nam Publishers, 2607 Military Road, Arlington, VA 22207, $25.00, email: canhnam@dc.net; tel. 703-525-4538.

First written in 1972; revised and added info from websites in November 2017—PT Lệ

Viết xong tại Virginia, August 20, 2017

Phạm Trọng Lệ